|

|

|

|

Excerpt from Utopia, Book 2.

[UTOPIAN VIEW OF RICHES, GOLD, AND JEWELS]

All things appear incredible to us, as they differ more or less from our own manners. Yet one who can judge aright will not wonder, that since their constitution differeth so materially from ours, their value of gold and silver also, should be measured by a very different standard. Having no use for money among themselves, but keeping it as a provision against events which seldom happen, and between which are generally long intervals, they value it no farther than it deserves, that is, in proportion to its use. Thus it is plain, they must prefer iron to either silver or gold. For we want iron nearly as much as fire and water, but nature hath marked out no use so essential for the other metals, that they may not easily be dispensed with. Man's folly hath enhanced the value of gold and silver because of their scarcity; whereas nature, like a kind parent, hath freely given us the best things, such as air, earth, and water, but hath hidden from us those which are vain and useless.

Were these metals to be laid-up in a tower, it would give birth to that foolish mistrust into which the people are apt to fall, and create suspicion that the prince and senate designed to sacrifice the public interest to their own advantage. Should they work them into vessels or other articles, they fear that the people might grow too fond of plate, and be unwilling to melt it again, if a war made it necessary. To prevent all these inconveniencies, they have fallen upon a plan, which agrees with their other policy, but is very different from ours; and which will hardly gain belief among us who value gold so much and lay it up so carefully.

They eat and drink from earthen ware or glass, which make an agreeable appearance though they be of little value; while their chamber-pots and close-stools are made of gold and silver; and this not only in their public halls, but in their private houses. Of the same metals they also make chains and fetters for their slaves; on some of whom, as a badge of infamy, they hang an ear-ring of gold, and make others wear a chain or a coronet of the same metal. And thus they take care, by all possible means, to render gold and silver of no esteem. Hence it is, that while other countries part with these metals as though one tore-out their bowels, the Utopians would look upon giving-in all they had of them, when occasion required, as parting only with a trifle, or as we should esteem the loss of a penny.

They find pearls on their coast, and diamonds and carbuncles on their rocks. They seek them not, but if they find them by chance, they polish them and give them to their children for ornaments, who delight in them during their childhood. But when they come to years of discretion, and see that none but children use such baubles, they lay them aside of their own accord; and would be as much ashamed to use them afterward, as grown children among us would be of their toys.

I never saw a more remarkable instance of the opposite impressions which different manners make on people, than I observed in the Anemolian ambassadors, who came to Amaurot when I was there. Coming to treat of affairs of great consequence, the deputies from several cities met to await their coming. The ambassadors of countries lying near Utopia, knowing their manners,—that fine clothes are in no esteem with them, that silk is despised, and gold a badge of infamy,—came very modestly clothed. But the Anemolians, who lie at a greater distance, having had little intercourse with them, understanding they were coarsely clothed and all in one dress, took it for granted that they had none of that finery among them, of which they made no use. Being also themselves a vain-glorious rather than a wise people, they resolved on this occasion to assume their grandest appearance, and astonish the poor Utopians with their splendour.

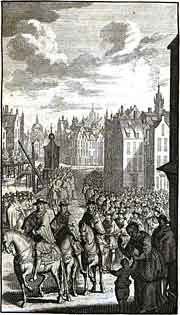

Thus three ambassadors made their entry with 100 attendants, all clad in garments of different colours, and the greater part in silk. The ambassadors themselves, who were of the nobility of their country, were in clothes of gold, adorned with massy chains and rings of gold. Their caps were covered with bracelets, thickly set with pearls and other gems. In a word, they were decorated in those very things, which, among the Utopians, are either badges of slavery, marks of infamy, or play-things for children.

Thus three ambassadors made their entry with 100 attendants, all clad in garments of different colours, and the greater part in silk. The ambassadors themselves, who were of the nobility of their country, were in clothes of gold, adorned with massy chains and rings of gold. Their caps were covered with bracelets, thickly set with pearls and other gems. In a word, they were decorated in those very things, which, among the Utopians, are either badges of slavery, marks of infamy, or play-things for children.

It was pleasant to behold, on one side, how big they looked in comparing their rich habits with the plain clothes of the Utopians, who came out in great numbers to see them make their entry; and on the other, how much they were mistaken in the impression which they expected this pomp would have made. The sight appeared so ridiculous to those who had not seen the customs of other countries, that, though they respected such as were meanly clad (as if they had been the ambassadors), when they saw the ambassadors themselves, covered with gold and chains, they looked upon them as slaves, and shewed them no respect. You might have heard children, who had thrown away their jewels, cry to their mothers, see that great fool, wearing pearls and gems as if he was yet a child; and the mothers as innocently replying, peace, this must be one of the ambassador's fools.

Others censured the fashion of their chains, and observed, they were of no use. For their slaves could easily break them; and they hung so loosely, that they thought it easy to throw them away. But when the ambassadors had been a day among them, and had seen the vast quantity of gold in their houses, as much despised by them as esteemed by others; when they beheld more gold and silver in the chains and fetters of one slave, than in all their ornaments; their crests fell, they were ashamed of their glory, and laid it aside; a resolution which they took, in consequence of engaging in free conversation with the Utopians, and discovering their sense of these things, and their other customs.

The Utopians wonder that any man should be so enamoured of the lustre of a jewel, when he can behold a star or the sun; or that he should value himself upon his cloth being made of a finer thread. For, however fine this thread, it was once the fleece of a sheep, which remained a sheep notwithstanding it wore it.

They marvel much to hear, that gold, in itself so useless, should be everywhere so much sought, that even men, for whom it was made, and by them hath its value, should be less esteemed. That a stupid fellow, with no more sense than a log, and as base as he is foolish, should have many wise and good men to serve him because he possesseth a heap of it. And that, should an accident, or a law-quirk (which sometimes produceth as great changes as chance herself), pass this wealth from the master to his meanest slave, he would soon become the servant of the other, as if he was an appendage of his wealth, and bound to follow it.

But they much more wonder at and detest the folly of those, who, when they see a rich man, though they owe him nothing, and are not in the least dependent on his bounty, are ready to pay him divine honours because he is rich; even though they know him at the same time to be so covetous and mean-spirited, that notwithstanding all his wealth, he will not part with one farthing of it to them as long as he liveth.

Cayley, Arthur, the Younger, ed. Memoirs of Sir Thomas More, &c.. Vol II.

London: Cadell and Davis, 1808. 78-83.

|

to the Works of Sir Thomas More |

Site copyright ©1996-2018 Anniina Jokinen. All

Rights Reserved.

Created by Anniina Jokinen

on June 1, 2009. Last updated December 11, 2018.

|

|

The Tudors

King Henry VII

Elizabeth of York

King Henry VIII

Queen Catherine of Aragon

Queen Anne Boleyn

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Anne of Cleves

Queen Catherine Howard

Queen Katherine Parr

King Edward VI

Queen Mary I

Queen Elizabeth I

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond

Renaissance English Writers

Bishop John Fisher

William Tyndale

Sir Thomas More

John Heywood

Thomas Sackville

Nicholas Udall

John Skelton

Sir Thomas Wyatt

Henry Howard

Hugh Latimer

Thomas Cranmer

Roger Ascham

Sir Thomas Hoby

John Foxe

George Gascoigne

John Lyly

Thomas Nashe

Sir Philip Sidney

Edmund Spenser

Richard Hooker

Robert Southwell

Robert Greene

George Peele

Thomas Kyd

Edward de Vere

Christopher Marlowe

Anthony Munday

Sir Walter Ralegh

Thomas Hariot

Thomas Campion

Mary Sidney Herbert

Sir John Davies

Samuel Daniel

Michael Drayton

Fulke Greville

Emilia Lanyer

William Shakespeare

Persons of Interest

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cromwell

John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester

Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio

Cardinal Reginald Pole

Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester

William Tyndale

Pico della Mirandola

Desiderius Erasmus

Christopher Saint-German

Thomas Linacre

William Grocyn

Hugh Latimer

Elizabeth Barton, the Nun of Kent

For more, visit Encyclopedia

Historical Events

Field of the Cloth of Gold, 1520

Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536

The Babington Plot, 1586

The Spanish Armada, 1588

Government

Oath of Supremacy

The Act of Supremacy, 1534

The First Act of Succession, 1534

The Third Act of Succession, 1544

The Ten Articles, 1536

The Six Articles, 1539

The Second Statute of Repeal, 1555

Images of London:

London in the time of Henry VII. MS. Roy. 16 F. ii.

London, 1510, earliest view in print

Map of England from Saxton's Descriptio Angliae, 1579

Location Map of Elizabethan London

Plan of the Bankside, Southwark, in Shakespeare's time

Detail of Norden's Map of the Bankside, 1593

Bull and Bear Baiting Rings from the Agas Map (1569-1590, pub. 1631)

Sketch of the Swan Theatre, c. 1596

Westminster in the Seventeenth Century, by Hollar

Visscher's Panoramic View of London, 1616. COLOR

For more, visit Encyclopedia

|

|