|

|

|

THE SIEGE OF CALAIS (1346-7)

NOWHERE does the continent of Europe approach Great Britain so closely as at the Straits of Dover, and when the

English sovereigns were full of the vain hope of obtaining the crown of France, or at least of regaining the

great possessions that their forefathers had owned as French nobles, there was no spot so coveted by them as

the fortress of Calais, the possession of which gave an entrance into France.

Thus it was that when, in 1346, Edward III had beaten Philippe VI at the

battle of Crecy, the first use he made of his victory was to march upon Calais, and

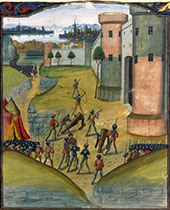

lay siege to it. The walls were exceedingly strong and solid, mighty defenses of masonry, of huge thickness

and like rocks for solidity, guarded it, and the king knew that it would be useless to attempt a direct assault.

Indeed, during all the middle ages, the modes of protecting fortifications were far more efficient than the

modes of attacking them. The walls could be made enormously massive, the towers raised to a great height, and

the defenders so completely sheltered by battlements that they could not easily be injured, and could take aim

from the top of their turrets, or from their loophole windows. The gates had absolute little castles of their

own, a moat flowed round the walls full of water, and only capable of being crossed by a drawbridge, behind

which the portcullis, a grating armed beneath with spikes, was always ready to drop from the archway of the

gate and close up the entrance. The only chance of taking a fortress by direct attack was to fill up the moat

with earth and faggots, and then raise ladders against the walls; or else to drive engines against the defenses,

battering-rams which struck them with heavy beams, mangonels which launched stones, sows

Indeed, during all the middle ages, the modes of protecting fortifications were far more efficient than the

modes of attacking them. The walls could be made enormously massive, the towers raised to a great height, and

the defenders so completely sheltered by battlements that they could not easily be injured, and could take aim

from the top of their turrets, or from their loophole windows. The gates had absolute little castles of their

own, a moat flowed round the walls full of water, and only capable of being crossed by a drawbridge, behind

which the portcullis, a grating armed beneath with spikes, was always ready to drop from the archway of the

gate and close up the entrance. The only chance of taking a fortress by direct attack was to fill up the moat

with earth and faggots, and then raise ladders against the walls; or else to drive engines against the defenses,

battering-rams which struck them with heavy beams, mangonels which launched stones, sows

whose arched wooden

backs protected troops of workmen who tried to undermine the wall, and moving towers consisting of a succession

of stages or shelves, filled with soldiers, and with a bridge with iron hooks, capable of being launched from

the highest story to the top of the battlements. The besieged could generally disconcert the battering-ram by

hanging beds or mattresses over the walls to receive the brunt of the blow, the sows could be crushed with heavy

stones, the towers burnt by well directed flaming missiles, the ladders overthrown, and in general the besiegers

suffered a great deal more damage than they could inflict. Cannon had indeed just been brought into use at the

battle of Crecy, but they only consisted of iron bars fastened together with hoops, and were as yet of little use,

and thus there seemed to be little danger to a well guarded city from any enemy outside the walls.

whose arched wooden

backs protected troops of workmen who tried to undermine the wall, and moving towers consisting of a succession

of stages or shelves, filled with soldiers, and with a bridge with iron hooks, capable of being launched from

the highest story to the top of the battlements. The besieged could generally disconcert the battering-ram by

hanging beds or mattresses over the walls to receive the brunt of the blow, the sows could be crushed with heavy

stones, the towers burnt by well directed flaming missiles, the ladders overthrown, and in general the besiegers

suffered a great deal more damage than they could inflict. Cannon had indeed just been brought into use at the

battle of Crecy, but they only consisted of iron bars fastened together with hoops, and were as yet of little use,

and thus there seemed to be little danger to a well guarded city from any enemy outside the walls.

King Edward arrived before the place with all his victorious army early in August, his good knights and squires

arrayed in glittering steel armor, covered with surcoats richly embroidered with their heraldic bearings; his

stout men-at-arms, each of whom was attended by three bold followers; and his archers, with their cross-bows

to shoot bolts, and long-bows to shoot arrows of a yard long, so that it used to be said that each went into

battle with three men's lives under his girdle, namely the three arrows he kept there ready to his hand. With

the king was his son, Edward, Prince of Wales, who had just won the golden spurs

of knighthood so gallantly at Crecy when only in his seventeenth year, and likewise the

famous Hainault knight, Sir Walter Mauny [or Manny], and all that was noblest and

bravest in England.

This whole glittering army, at their head the king's great royal standard bearing the golden lilies of France

quartered with the lions of England, and each troop guided by the square banner, swallow-tailed pennon or

pointed pennoncel of their leader, came marching to the gates of Calais, above which floated the blue standard

of France with its golden flowers, and with it the banner of the governor, Sir Jean de Vienne. A herald, in a

rich long robe embroidered with the arms of England, rode up to the gate, a trumpet sounding before him, and

called upon Sir Jean de Vienne to give up the place to Edward, King of England, and of France, as he claimed

to be. Sir Jean made answer that he held the town for Philippe, King of France, and that he would defend it

to the last; the herald rode back again and the English began the siege of the city.

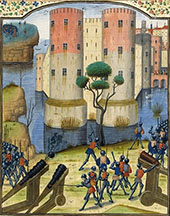

At first they only encamped, and the people of Calais must have seen the whole plain covered with the white

canvas tents, marshalled round the ensigns of the leaders, and here and there a more gorgeous one displaying

the colors of the owner. Still there was no attack upon the walls. The warriors were to be seen walking about

in the leathern suits they wore under their armor; or if a party was to be seen with their coats of mail on,

helmet on head, and lance in hand, it was not against Calais that they came; they rode out into the country,

and by and by might be seen driving back before them herds of cattle and flocks of sheep or pigs that they

had seized and taken away from the poor peasants; and at night the sky would show red lights where farms and

homesteads had been set on fire. After a time, in front of the tents, the English were to be seen hard at work

with beams and boards, setting up huts for themselves, and thatching them over with straw or broom.

These wooden houses were all ranged in regular streets, and there was a market-place in the midst, whither

every Saturday came farmers and butchers to sell corn and meat, and hay for the horses; and the English

merchants and Flemish weavers would come by sea and by land to bring cloth, bread, weapons, and everything

that could be needed to be sold in this warlike market.

At first they only encamped, and the people of Calais must have seen the whole plain covered with the white

canvas tents, marshalled round the ensigns of the leaders, and here and there a more gorgeous one displaying

the colors of the owner. Still there was no attack upon the walls. The warriors were to be seen walking about

in the leathern suits they wore under their armor; or if a party was to be seen with their coats of mail on,

helmet on head, and lance in hand, it was not against Calais that they came; they rode out into the country,

and by and by might be seen driving back before them herds of cattle and flocks of sheep or pigs that they

had seized and taken away from the poor peasants; and at night the sky would show red lights where farms and

homesteads had been set on fire. After a time, in front of the tents, the English were to be seen hard at work

with beams and boards, setting up huts for themselves, and thatching them over with straw or broom.

These wooden houses were all ranged in regular streets, and there was a market-place in the midst, whither

every Saturday came farmers and butchers to sell corn and meat, and hay for the horses; and the English

merchants and Flemish weavers would come by sea and by land to bring cloth, bread, weapons, and everything

that could be needed to be sold in this warlike market.

The governor, Sir Jean de Vienne, began to perceive that the king did not mean to waste his men by making vain

attacks on the strong walls of Calais, but to shut up the entrance by land, and watch the coast by sea so as to

prevent any provisions from being taken in, and so to starve him into surrendering. Sir Jean de Vienne, however,

hoped that before he should be entirely reduced by famine, the King of France would be able to get together

another army and come to his relief, and at any rate he was determined to do his duty, and hold out for his

master to the last. But as food was already beginning to grow scarce, he was obliged to turn out such persons

as could not fight and had no stores of their own, and so one Wednesday morning he caused all the poor to be

brought together, men, women, and children, and sent them all out of the town, to the number of 1,700. It was

probably the truest mercy, for he had no food to give them, and they could only have starved miserably within

the town, or have hindered him from saving it for his sovereign; but to them it was dreadful to be driven out

of house and home, straight down upon the enemy, and they went along weeping and wailing, till the English

soldiers met them and asked why they had come out. They answered that they had been put out because they had

nothing to eat, and their sorrowful famished looks gained pity for them. King Edward sent orders that not only

should they go safely through his camp, but that they should all rest, and have the first hearty dinner that

they had eaten for many a day, and he sent every one a small sum of money before they left the camp, so that

many of them went on their way praying aloud for the enemy who had been so kind to them.

A great deal happened whilst King Edward kept watch in his wooden town and the citizens of Calais guarded their

walls. England was invaded by King David II of Scotland, with a great army, and the good

Queen Philippa, who was left to govern at home in the name of her little son

Lionel, assembled all the forces that were left at home, and sent them to meet

him. And one autumn day, a ship crossed the Straits of Dover, and a messenger brought King Edward letters from

his queen to say that the Scots army had been entirely defeated at Nevil's Cross, near Durham, and that their

king was a prisoner, but that he had been taken by a squire named John Copeland, who would not give him up to her.

King Edward sent letters to John Copeland to come to him at Calais, and when the squire had made his journey,

the king took him by the hand saying, "Ha! welcome, my squire, who by his valor has captured our adversary the

King of Scotland." Copeland, falling on one knee, replied, "If God, out of His great kindness, has given me the

King of Scotland, no one ought to be jealous of it, for God can, when He pleases, send His grace to a poor squire

as well as to a great lord. Sir, do not take it amiss if I did not surrender him to the orders of my lady queen,

for I hold my lands of you, and my oath is to you, not to her." The king was not displeased with his squire's

sturdiness, but made him a knight, gave him a pension of 5001. a year, and desired him to surrender his

prisoner to the queen, as his own representative. This was accordingly done, and King David was lodged in the

Tower of London.

Soon after, three days before All Saints' Day, there was a large and gay fleet to be seen crossing from the white

cliffs of Dover, and the king, his son, and his knights rode down to the landing-place to welcome plump, fair-haired

Queen Philippa, and all her train of ladies, who had come in great numbers to visit their husbands, fathers, or

brothers in the wooden town. Then there was a great court, and numerous feasts and dances, and the knights and

squires were constantly striving who could do the bravest deed of prowess to please the ladies. The King of France

had placed numerous knights and men-at-arms in the neighboring towns and castles, and there were constant fights

whenever the English went out foraging, and many bold deeds that were much admired were done. The great point was

to keep provisions out of the town, and there was much fighting between the French who tried to bring in supplies,

and the English who intercepted them. Very little was brought in by land, and Sir Jean de Vienne and his garrison

would have been quite starved but for two sailors of Abbeville, named Marant and Mestriel, who knew the coast

thoroughly, and often, in the dark autumn evenings, would guide in a whole fleet of little boats, loaded with bread

and meat for the starving men within the city. They were often chased by King Edward's vessels, and were sometimes

very nearly taken, but they always managed to escape, and thus they still enabled the garrison to hold out.

So all the winter passed, Christmas was kept with brilliant feasting and high merriment by the king and his queen

in their wooden palace outside, and with lean cheeks and scanty fare by the besieged within. Lent was strictly

observed perforce by the besieged, and Easter brought a betrothal in the English camp; a very unwilling one on the

part of the bridegroom, the young Count of Flanders, who loved the French much better than the English, and had

only been tormented into giving his consent by his unruly vassals because they depended on the wool of English

sheep for their cloth works. So, though King Edward's daughter Isabel was a beautiful fair-haired girl of fifteen,

the young count would scarcely look at her; and in the last week before the marriage-day, while her robes and her

jewels were being prepared, and her father and mother were arranging the presents they should make to all their

court on the wedding-day, the bridegroom, when out hawking, gave his attendants the slip, and galloped off to

Paris, where he was welcomed by King Philippe.

This made Edward very wrathful, and more than ever determined to take Calais. About Whitsuntide he completed a

great wooden castle upon the seashore, and placed in it numerous warlike engines, with forty men-at-arms and 200

archers, who kept such a watch upon the harbor that not even the two Abbeville sailors could enter it, without

having their boats crushed and sunk by the great stones that the mangonels launched upon them. The townspeople

began to feel what hunger really was, but their spirits were kept up by the hope that their king was at last

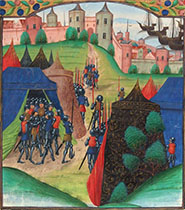

collecting an army for their rescue. And Philippe did collect all his forces, a great and noble army, and came

one night to the hill of Sangate, just behind the English army, the knights' armor glancing and their pennons

flying in the moonlight, so as to be a beautiful sight to the hungry garrison who could see the white tents

pitched upon the hillside. Still there were but two roads by which the French could reach their friends in

the town—one along the seacoast, the other by a marshy road higher up the country, and there was but one

bridge by which the river could be crossed. The English king's fleet could prevent any troops from passing

along the coast road, the Earl of Derby guarded the bridge, and there was

a great tower, strongly fortified, close upon Calais.

There were a few skirmishes, but the French king, finding it difficult to

force his way to relieve the town, sent a party of knights with a challenge to King Edward to come out of

his camp and do battle upon a fair field. To this Edward made answer, that he had been nearly a year before

Calais, and had spent large sums of money on the siege, and that he had nearly become master of the place,

so that he had no intention of coming out only to gratify his adversary, who must try some other road if he

could not make his way in by that before him. Three days were spent in parleys, and then, without the slightest

effort to rescue the brave, patient men within the town, away went King Philippe of France, with all his men,

and the garrison saw the host that had crowded the hill of Sangate melt away like a summer cloud.

There were a few skirmishes, but the French king, finding it difficult to

force his way to relieve the town, sent a party of knights with a challenge to King Edward to come out of

his camp and do battle upon a fair field. To this Edward made answer, that he had been nearly a year before

Calais, and had spent large sums of money on the siege, and that he had nearly become master of the place,

so that he had no intention of coming out only to gratify his adversary, who must try some other road if he

could not make his way in by that before him. Three days were spent in parleys, and then, without the slightest

effort to rescue the brave, patient men within the town, away went King Philippe of France, with all his men,

and the garrison saw the host that had crowded the hill of Sangate melt away like a summer cloud.

August had come again, and they had suffered privation for a whole year for the sake of the king who deserted

them at their utmost need. They were in so grievous a state of hunger and distress that the hardiest could

endure no more, for ever since Whitsuntide no fresh provisions had reached them. The governor, therefore, went

to the battlements and made signs that he wished to hold a parley, and the king appointed Lord Basset and

Sir Walter Mauny to meet him, and appoint the terms of surrender. The governor

owned that the garrison was reduced to the greatest extremity of distress, and requested that the king would

be contented with obtaining the city and fortress, leaving the soldiers and inhabitants to depart in peace.

But Sir Walter Mauny was forced to make answer that the king, his lord, was so much enraged at the delay and

expense that Calais had cost him, that he would only consent to receive the whole on unconditional terms,

leaving him free to slay, or to ransom, or make prisoners whomsoever he pleased, and he was known to consider

that there was a heavy reckoning to pay, both for the trouble the siege had cost him and the damage the

Calesians had previously done to his ships. The brave answer was: "These conditions are too hard for us.

We are but a small number of knights and squires, who have loyally served our lord and master as you would

have done, and have suffered much ill and disquiet, but we will endure far more than any man has done in such

a post, before we consent that the smallest boy in the town shall fare worse than ourselves. I therefore

entreat you, for pity's sake, to return to the king and beg him to have compassion, for I have such an opinion

of his gallantry that I think he will alter his mind."

The king's mind seemed, however, sternly made up; and all that Sir Walter Mauny and the barons of the council

could obtain from him was that he would pardon the garrison and townsmen on condition that six of the chief

citizens should present themselves to him, coming forth with bare feet and heads, with halters round their necks,

carrying the keys of the town, and becoming absolutely his own to punish for their obstinacy as he should think

fit. On hearing this reply, Sir Jean de Vienne begged Sir Walter Mauny to wait till he could consult the citizens,

and, repairing to the market-place, he caused a great bell to be rung, at sound of which all the inhabitants came

together in the town-hall. When he told them of these hard terms he could not refrain from weeping bitterly, and

wailing and lamentation arose all round him. Should all starve together, or sacrifice their best and most honored

after all suffering in common so long?

Then a voice was heard; it was that of the richest burgher in the town, Eustache de St. Pierre. "Messieurs, high

and low," he said, "it would be a sad pity to suffer so many people to die through hunger, if it could be prevented;

and to hinder it would be meritorious in the eyes of our Saviour. I have such faith and trust in finding grace before

God, if I die to save my townsmen, that I name myself as first of the six." As the burgher ceased, his fellow-townsmen

wept aloud, and many, amid tears and groans, threw themselves at his feet in a transport of grief and gratitude.

Another citizen, very rich and respected, rose up and said, "I will be second to my comrade, Eustache." His name was

Jean Daire. After him, Jacques Wissant, another very rich man, offered himself as companion to these, who were both

his cousins; and his brother Pierre would not be left behind: and two more, unnamed, made up this gallant band of men

willing to offer their lives for the rescue of their fellow-townsmen.

Sir Jean de Vienne mounted a little horse—for he had been wounded, and was still lame—and came to the gate

with them, followed by all the people of the town, weeping and wailing, yet, for their own sakes and their children's,

not daring to prevent the sacrifice. The gates were opened, the governor and the six passed out, and the gates were

again shut behind them. Sir Jean then rode up to Sir Walter Mauny, and told him how these burghers had voluntarily

offered themselves, begging him to do all in his power to save them; and Sir Walter promised with his whole heart to

plead their cause. De Vienne then went back into the town, full of heaviness and anxiety; and the six citizens were

led by Sir Walter to the presence of the king, in his full court. They all knelt down, and the foremost said: "Most

gallant king, you see before you six burghers of Calais, who have all been capital merchants, and who bring you the

keys of the castle and town. We yield ourselves to your absolute will and pleasure, in order to save the remainder of

the inhabitants of Calais, who have suffered much distress and misery. Condescend, therefore, out of your nobleness

of mind, to have pity on us."

Strong emotion was excited among all the barons and knights who stood round, as they saw the resigned countenances,

pale and thin with patiently-endured hunger, of these venerable men, offering themselves in the cause of their

fellow-townsmen. Many tears of pity were shed; but the king still showed himself implacable, and commanded that they

should be led away, and their heads stricken off. Sir Walter Mauny interceded for them with all his might, even

telling the king that such an execution would tarnish his honor, and that reprisals would be made on his own

garrisons; and all the nobles joined in entreating pardon for the citizens, but still without effect; and the headsman

had been actually sent for, when Queen Philippa, her eyes streaming with tears, threw

herself on her knees amongst the captives, and said, "Ah, gentle sir, since I have crossed the sea with much danger

to see you, I have never asked you one favor; now I beg as a boon to myself, for the sake of the Son of the Blessed

Mary, and for your love to me, that you will be merciful to these men!"

had been actually sent for, when Queen Philippa, her eyes streaming with tears, threw

herself on her knees amongst the captives, and said, "Ah, gentle sir, since I have crossed the sea with much danger

to see you, I have never asked you one favor; now I beg as a boon to myself, for the sake of the Son of the Blessed

Mary, and for your love to me, that you will be merciful to these men!"

For some time the king looked at her in silence; then he exclaimed: "Dame, dame, would that you had been anywhere

than here! You have entreated in such a manner that I cannot refuse you; I therefore give these men to you, to do

as you please with." Joyfully did Queen Philippa conduct the six citizens to her own apartments, where she made them

welcome, sent them new garments, entertained them with a plentiful dinner, and dismissed them each with a gift of

six nobles. After this, Sir Walter Mauny entered the city, and took possession of it; retaining Sir Jean de Vienne

and the other knights and squires till they should ransom themselves, and sending out the old French inhabitants;

for the king was resolved to people the city entirely with English, in order to gain a thoroughly strong hold of

this first step in France.

The king and queen took up their abode in the city; and the houses of Jean Daire were, it appears, granted to the

queen—perhaps, because she considered the man himself as her charge, and wished to secure them for him—and

her little daughter Margaret was, shortly after, born in one of his houses. Eustache de St. Pierre was taken into

high favor, and was placed in charge of the new citizens whom the king placed in the city.

Indeed, as this story is told by no chronicler but Froissart, some have doubted of it, and thought the violent

resentment thus imputed to Edward III inconsistent with his general character; but it is evident that the men of

Calais had given him strong provocation by attacks on his shipping—piracies which are not easily forgiven—and

that he considered that he had a right to make an example of them. It is not unlikely that he might, after all,

have intended to forgive them, and have given the queen the grace of obtaining their pardon, so as to excuse himself

from the fulfillment of some over-hasty threat. But, however this may have been, nothing can lessen the glory of

the six grave and patient men who went forth, by their own free will, to meet what might be a cruel and disgraceful

death, in order to obtain the safety of their fellow townsmen.

Excerpted from:

Yonge, Charlotte M. "The Noble Burghers of Calais." The Junior Classics. Vol VII.

New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1912. 99-113.

Other Local Resources:

Books for further study:

Allmand, Christopher. The Hundred Years War: England and France at War.

Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Seward, Desmond. The Hundred Years War: The English in France 1337-1453.

Penguin, 1999.

| to Luminarium Encyclopedia |

Site ©1996-2023 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

This page was created on January 3, 2018. Last updated March 5, 2023.

|

Index of Encyclopedia Entries:

Medieval Cosmology

Prices of Items in Medieval England

Edward II

Isabella of France, Queen of England

Piers Gaveston

Thomas of Brotherton, E. of Norfolk

Edmund of Woodstock, E. of Kent

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Lancaster, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster

Roger Mortimer, Earl of March

Hugh le Despenser the Younger

Bartholomew, Lord Burghersh, elder

Hundred Years' War (1337-1453)

Edward III

Philippa of Hainault, Queen of England

Edward, Black Prince of Wales

John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall

The Battle of Crécy, 1346

The Siege of Calais, 1346-7

The Battle of Poitiers, 1356

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York

Thomas of Woodstock, Gloucester

Richard of York, E. of Cambridge

Richard Fitzalan, 3. Earl of Arundel

Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March

The Good Parliament, 1376

Richard II

The Peasants' Revolt, 1381

Lords Appellant, 1388

Richard Fitzalan, 4. Earl of Arundel

Archbishop Thomas Arundel

Thomas de Beauchamp, E. Warwick

Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford

Ralph Neville, E. of Westmorland

Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk

Edmund Mortimer, 3. Earl of March

Roger Mortimer, 4. Earl of March

John Holland, Duke of Exeter

Michael de la Pole, E. Suffolk

Hugh de Stafford, 2. E. Stafford

Henry IV

Edward, Duke of York

Edmund Mortimer, 5. Earl of March

Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland

Sir Henry Percy, "Harry Hotspur"

Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester

Owen Glendower

The Battle of Shrewsbury, 1403

Archbishop Richard Scrope

Thomas Mowbray, 3. E. Nottingham

John Mowbray, 2. Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Fitzalan, 5. Earl of Arundel

Henry V

Thomas, Duke of Clarence

John, Duke of Bedford

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

Richard, Earl of Cambridge

Henry, Baron Scrope of Masham

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Montacute, E. Salisbury

Richard Beauchamp, E. of Warwick

Henry Beauchamp, Duke of Warwick

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter

Cardinal Henry Beaufort

John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset

Sir John Fastolf

John Holland, 2. Duke of Exeter

Archbishop John Stafford

Archbishop John Kemp

Catherine of Valois

Owen Tudor

John Fitzalan, 7. Earl of Arundel

John, Lord Tiptoft

Charles VII, King of France

Joan of Arc

Louis XI, King of France

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

The Battle of Agincourt, 1415

The Battle of Castillon, 1453

The Wars of the Roses 1455-1485

Causes of the Wars of the Roses

The House of Lancaster

The House of York

The House of Beaufort

The House of Neville

The First Battle of St. Albans, 1455

The Battle of Blore Heath, 1459

The Rout of Ludford, 1459

The Battle of Northampton, 1460

The Battle of Wakefield, 1460

The Battle of Mortimer's Cross, 1461

The 2nd Battle of St. Albans, 1461

The Battle of Towton, 1461

The Battle of Hedgeley Moor, 1464

The Battle of Hexham, 1464

The Battle of Edgecote, 1469

The Battle of Losecoat Field, 1470

The Battle of Barnet, 1471

The Battle of Tewkesbury, 1471

The Treaty of Pecquigny, 1475

The Battle of Bosworth Field, 1485

The Battle of Stoke Field, 1487

Henry VI

Margaret of Anjou

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York

Edward IV

Elizabeth Woodville

Richard Woodville, 1. Earl Rivers

Anthony Woodville, 2. Earl Rivers

Jane Shore

Edward V

Richard III

George, Duke of Clarence

Ralph Neville, 2. Earl of Westmorland

Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick

Edward Neville, Baron Bergavenny

William Neville, Lord Fauconberg

Robert Neville, Bishop of Salisbury

John Neville, Marquis of Montagu

George Neville, Archbishop of York

John Beaufort, 1. Duke Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2. Duke Somerset

Henry Beaufort, 3. Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 4. Duke Somerset

Margaret Beaufort

Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond

Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke

Humphrey Stafford, D. Buckingham

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

Humphrey Stafford, E. of Devon

Thomas, Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby

Sir William Stanley

Archbishop Thomas Bourchier

Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex

John Mowbray, 3. Duke of Norfolk

John Mowbray, 4. Duke of Norfolk

John Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Henry Percy, 2. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 3. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 4. E. Northumberland

William, Lord Hastings

Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter

William Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford

Thomas de Clifford, 8. Baron Clifford

John de Clifford, 9. Baron Clifford

John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester

Thomas Grey, 1. Marquis Dorset

Sir Andrew Trollop

Archbishop John Morton

Edward Plantagenet, E. of Warwick

John Talbot, 2. E. Shrewsbury

John Talbot, 3. E. Shrewsbury

John de la Pole, 2. Duke of Suffolk

John de la Pole, E. of Lincoln

Edmund de la Pole, E. of Suffolk

Richard de la Pole

John Sutton, Baron Dudley

James Butler, 5. Earl of Ormonde

Sir James Tyrell

Edmund Grey, first Earl of Kent

George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent

John, 5th Baron Scrope of Bolton

James Touchet, 7th Baron Audley

Walter Blount, Lord Mountjoy

Robert Hungerford, Lord Moleyns

Thomas, Lord Scales

John, Lord Lovel and Holand

Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell

Sir Richard Ratcliffe

William Catesby

Ralph, 4th Lord Cromwell

Jack Cade's Rebellion, 1450

Tudor Period

King Henry VII

Queen Elizabeth of York

Arthur, Prince of Wales

Lambert Simnel

Perkin Warbeck

The Battle of Blackheath, 1497

King Ferdinand II of Aragon

Queen Isabella of Castile

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

King Henry VIII

Queen Catherine of Aragon

Queen Anne Boleyn

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Anne of Cleves

Queen Catherine Howard

Queen Katherine Parr

King Edward VI

Queen Mary I

Queen Elizabeth I

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond

Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

James IV, King of Scotland

The Battle of Flodden Field, 1513

James V, King of Scotland

Mary of Guise, Queen of Scotland

Mary Tudor, Queen of France

Louis XII, King of France

Francis I, King of France

The Battle of the Spurs, 1513

Field of the Cloth of Gold, 1520

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador

The Siege of Boulogne, 1544

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex

Thomas, Lord Audley

Thomas Wriothesley, E. Southampton

Sir Richard Rich

Edward Stafford, D. of Buckingham

Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire

George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford

John Russell, Earl of Bedford

Thomas Grey, 2. Marquis of Dorset

Henry Grey, D. of Suffolk

Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester

George Talbot, 4. E. Shrewsbury

Francis Talbot, 5. E. Shrewsbury

Henry Algernon Percy,

5th Earl of Northumberland

Henry Algernon Percy,

6th Earl of Northumberland

Ralph Neville, 4. E. Westmorland

Henry Neville, 5. E. Westmorland

William Paulet, Marquis of Winchester

Sir Francis Bryan

Sir Nicholas Carew

John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford

Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral

Edward Seymour, Protector Somerset

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury

Henry Pole, Lord Montague

Sir Geoffrey Pole

Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Bourchier, 2. Earl of Essex

Robert Radcliffe, 1. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 2. Earl of Sussex

George Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon

Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter

George Neville, Baron Bergavenny

Sir Edward Neville

William, Lord Paget

William Sandys, Baron Sandys

William Fitzwilliam, E. Southampton

Sir Anthony Browne

Sir Thomas Wriothesley

Sir William Kingston

George Brooke, Lord Cobham

Sir Richard Southwell

Thomas Fiennes, 9th Lord Dacre

Sir Francis Weston

Henry Norris

Lady Jane Grey

Sir Thomas Arundel

Sir Richard Sackville

Sir William Petre

Sir John Cheke

Walter Haddon, L.L.D

Sir Peter Carew

Sir John Mason

Nicholas Wotton

John Taylor

Sir Thomas Wyatt, the Younger

Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio

Cardinal Reginald Pole

Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester

Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London

Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London

John Hooper, Bishop of Gloucester

John Aylmer, Bishop of London

Thomas Linacre

William Grocyn

Archbishop William Warham

Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham

Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester

Edward Fox, Bishop of Hereford

Pope Julius II

Pope Leo X

Pope Clement VII

Pope Paul III

Pope Pius V

Pico della Mirandola

Desiderius Erasmus

Martin Bucer

Richard Pace

Christopher Saint-German

Thomas Tallis

Elizabeth Barton, the Nun of Kent

Hans Holbein, the Younger

The Sweating Sickness

Dissolution of the Monasteries

Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536

Robert Aske

Anne Askew

Lord Thomas Darcy

Sir Robert Constable

Oath of Supremacy

The Act of Supremacy, 1534

The First Act of Succession, 1534

The Third Act of Succession, 1544

The Ten Articles, 1536

The Six Articles, 1539

The Second Statute of Repeal, 1555

The Act of Supremacy, 1559

Articles Touching Preachers, 1583

Queen Elizabeth I

William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Nicholas Bacon

Sir Thomas Bromley

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick

Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon

Sir Thomas Egerton, Viscount Brackley

Sir Francis Knollys

Katherine "Kat" Ashley

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester

George Talbot, 6. E. of Shrewsbury

Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury

Gilbert Talbot, 7. E. of Shrewsbury

Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Robert Sidney

Archbishop Matthew Parker

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich

Sir Christopher Hatton

Edward Courtenay, E. Devonshire

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Thomas Radcliffe, 3. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 4. Earl of Sussex

Robert Radcliffe, 5. Earl of Sussex

William Parr, Marquis of Northampton

Henry Wriothesley, 2. Southampton

Henry Wriothesley, 3. Southampton

Charles Neville, 6. E. Westmorland

Thomas Percy, 7. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 8. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 9. E. Nothumberland

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

Charles, Lord Howard of Effingham

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk

Henry Howard, 1. Earl of Northampton

Thomas Howard, 1. Earl of Suffolk

Henry Hastings, 3. E. of Huntingdon

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland

Francis Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland

Henry FitzAlan, 12. Earl of Arundel

Thomas, Earl Arundell of Wardour

Edward Somerset, E. of Worcester

William Davison

Sir Walter Mildmay

Sir Ralph Sadler

Sir Amyas Paulet

Gilbert Gifford

Anthony Browne, Viscount Montague

François, Duke of Alençon & Anjou

Mary, Queen of Scots

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell

Anthony Babington and the Babington Plot

John Knox

Philip II of Spain

The Spanish Armada, 1588

Sir Francis Drake

Sir John Hawkins

William Camden

Archbishop Whitgift

Martin Marprelate Controversy

John Penry (Martin Marprelate)

Richard Bancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury

John Dee, Alchemist

Philip Henslowe

Edward Alleyn

The Blackfriars Theatre

The Fortune Theatre

The Rose Theatre

The Swan Theatre

Children's Companies

The Admiral's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men

Citizen Comedy

The Isle of Dogs, 1597

Common Law

Court of Common Pleas

Court of King's Bench

Court of Star Chamber

Council of the North

Fleet Prison

Assize

Attainder

First Fruits & Tenths

Livery and Maintenance

Oyer and terminer

Praemunire

The Stuarts

King James I of England

Anne of Denmark

Henry, Prince of Wales

The Gunpowder Plot, 1605

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset

Arabella Stuart, Lady Lennox

William Alabaster

Bishop Hall

Bishop Thomas Morton

Archbishop William Laud

John Selden

Lucy Harington, Countess of Bedford

Henry Lawes

King Charles I

Queen Henrietta Maria

Long Parliament

Rump Parliament

Kentish Petition, 1642

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford

John Digby, Earl of Bristol

George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax

Robert Devereux, 3rd E. of Essex

Robert Sidney, 2. E. of Leicester

Algernon Percy, E. of Northumberland

Henry Montagu, Earl of Manchester

Edward Montagu, 2. Earl of Manchester

The Restoration

King Charles II

King James II

Test Acts

Greenwich Palace

Hatfield House

Richmond Palace

Windsor Palace

Woodstock Manor

The Cinque Ports

Mermaid Tavern

Malmsey Wine

Great Fire of London, 1666

Merchant Taylors' School

Westminster School

The Sanctuary at Westminster

"Sanctuary"

Images:

Chart of the English Succession from William I through Henry VII

Medieval English Drama

London c1480, MS Royal 16

London, 1510, the earliest view in print

Map of England from Saxton's Descriptio Angliae, 1579

London in late 16th century

Location Map of Elizabethan London

Plan of the Bankside, Southwark, in Shakespeare's time

Detail of Norden's Map of the Bankside, 1593

Bull and Bear Baiting Rings from the Agas Map (1569-1590, pub. 1631)

Sketch of the Swan Theatre, c. 1596

Westminster in the Seventeenth Century, by Hollar

Visscher's View of London, 1616

Larger Visscher's View in Sections

c. 1690. View of London Churches, after the Great Fire

The Yard of the Tabard Inn from Thornbury, Old and New London

|

|