|

|

|

The Battle of Crécy, fought between Edward III of England and King Philip VI of France,

was one of the most important battles in the Hundred Years' War. Sources disagree over

the size of the armies, the English army cited as numbering 10-34,000 strong, the French

army 35-120,000 strong. Due to their organization, their cannons, and their longbowmen,

the English won the day. The new weapons and tactics employed marked an end to the

era of the feudal warfare of knights on horseback. —AJ.

|

BATTLE OF CRÉCY (August 26, 1346)

by David Hume

"IT is natural to think that Philip, at the head of so vast an army, was impatient to take revenge on the English, and to prevent

the disgrace to which he must be exposed if an inferior enemy should be allowed, after ravaging so great a part of his kingdom,

to escape with impunity. Edward also was sensible that such must be the object of the French monarch; and as he had advanced

but a little way before his enemy, he saw the danger of precipitating his march over the plains of Picardy, and of exposing

his rear to the insults of the numerous cavalry, in which the French camp abounded. He took, therefore, a prudent resolution:

he chose his ground with advantage, near the village of Crecy; he disposed his army in excellent order; he determined to await

in tranquillity the arrival of the enemy; and he hoped that their eagerness to engage and to prevent his retreat after all their

past disappointments, would hurry them on to some rash and ill-concerted action.

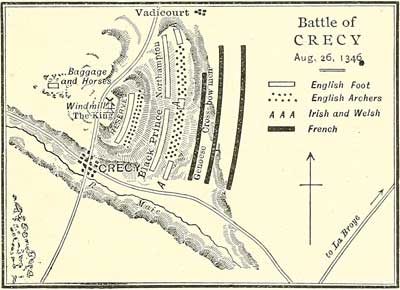

He drew up his army on a gentle ascent, and divided them into three lines: the first was commanded by the

Prince of Wales, and, under him, by the Earls of Warwick and

Oxford, by Harcourt, and by the Lords Chandos, Holland, and other

noblemen: the Earls of Arundel and Northampton, with the Lords

Willoughby, Basset, Roos, and Sir Lewis Tufton, were at the head of the second line: he took to himself the command of the

third division, by which he purposed either to bring succor to the two first lines, or to secure a retreat in case of any

misfortune, or to push his advantages against the enemy. He had likewise the precaution to throw up trenches on his flanks,

in order to secure himself from the numerous bodies of the French, who might assail him from that quarter; and he placed all

his baggage behind him in a wood, which he also secured by an intrenchment.

It is related by some historians that Edward, besides the resources which he found in his own genius and presence of mind,

employed also a new invention against the enemy, and placed in his front some pieces of artillery, the first that had yet

been made use of on any remarkable occasion in Europe. The invention of artillery was at this time known in France as well

as in England; but Philip, in his hurry to overtake the enemy, had probably left his cannon behind him, which he regarded

as a useless incumbrance. All his other movements discovered the same imprudence and precipitation. Impelled by anger, a

dangerous counsellor, and trusting to the great superiority of his numbers, he thought that all depended on forcing an

engagement with the English; and that, if he could once reach the enemy in their retreat, the victory on his side was certain

and inevitable. He made a hasty march, in some confusion, from Abbeville; but after he had advanced above two leagues,

some gentlemen, whom he had sent before to take a view of the enemy, returned to him, and brought him intelligence that

they had seen the English drawn up in great order, and awaiting his arrival. They therefore advised him to defer the combat

till the ensuing day, when his army would have recovered from their fatigue, and might be disposed into better order than

their present hurry had permitted them to observe.

Philip assented to this counsel; but the former precipitation of his march, and the impatience of the French nobility,

made it impracticable for him to put it in execution. One division French pressed upon another: orders to stop were not

seasonably conveyed to all of them: this immense body was not governed by sufficient discipline to be manageable; and the

French army, imperfectly formed into three lines, arrived, already fatigued and disordered, in presence of the enemy.

The first line, consisting of 15,000 Genoese crossbow-men, was commanded by Anthony Doria and Charles Grimaldi: the second

was led by the Count of Alençon, brother to the King: the King himself was at the head of the third. Besides the

French monarch, there were no less than three crowned heads in this engagement: the King of Bohemia, the King of the Romans,

his son, and the King of Majorca; with all the nobility and great vassals of the crown of France. The army now consisted

of above 120,000 men, more than three times the number of the enemy. But the prudence of one man was superior to the

advantage of all this force and splendor.

The English, on the approach of the enemy, kept their ranks firm and immovable; and the Genoese first began the attack.

There had happened, a little before the engagement, a thunder-shower, which had moistened and relaxed the strings of

the Genoese crossbows; their arrows, for this reason, fell short of the enemy. The English archers, taking their bows

out of their cases, poured in a shower of arrows upon this multitude who were opposed to them, and soon threw them into

disorder. The Genoese fell back upon the heavy-armed cavalry of the Count of Alençon; who, enraged at their cowardice,

ordered his troops to put them to the sword. The artillery fired amid the crowd; the English archers continued to send in

their arrows among them; and nothing was to be seen in that vast body but hurry and confusion, terror and dismay.

The young Prince of Wales had the presence of mind to take advantage of this situation,

and to lead on his line to the charge. The French cavalry, however, recovering somewhat their order, and encouraged

by the example of their leader, made a stout resistance; and having at last cleared themselves of the Genoese runaways,

advanced upon their enemies, and by their superior numbers began to hem them round. The Earls of

Arundel and Northampton now advanced their line to sustain

the Prince, who, ardent in his first feats of arms, set an example of valor which was imitated by all his followers.

The battle became, for some time, hot and dangerous; and the Earl of Warwick,

apprehensive of the event from the superior numbers of the French, despatched a messenger to the King, and entreated

him to send succors to the relief of the forcements.

Edward had chosen his station on the top of the hill; and he surveyed in tranquillity the scene of action. When the

messenger accosted him, his first question was, whether the Prince was slain or wounded? On receiving an answer in the

negative, "Return," said he, "to my son, and tell him that I reserve the honor of the day to him: I am confident that

he will show himself worthy of the honor of knighthood which I so lately conferred upon him: he will be able, without

my assistance, to repel the enemy." This speech being reported to the Prince and his attendants, inspired them with

fresh courage: they made an attack with redoubled vigor on the French, in which the Count of Alençon was slain;

that whole line of cavalry was thrown into disorder; the riders were killed or dismounted; the Welsh infantry rushed

into the throng, and with their long knives cut the throats of all who had fallen; nor was any quarter given that day

by the victors.

The King of France advanced in vain with the rear to sustain the line commanded by his brother: he found them already

discomfited; and the example of their rout increased the confusion which was before but too prevalent in his own body.

He had himself a horse killed under him: he was remounted; and though left almost alone, he seemed still determined

to maintain the combat; when John of Hainault seized the reins of his bridle, turned about his horse, and carried

him off the field of battle. The whole French army took to flight, and was followed and put to the sword, without

mercy, by the enemy; till the darkness of the night put an end to the pursuit. The King, on his return to the camp,

flew into the arms of the Prince of Wales, and exclaimed, "My brave son! Persevere in your honorable cause: you are

my son; for valiantly, have you acquitted yourself to-day: you have shown yourself worthy of empire."

This battle, which is known by the name of the battle of Crecy, began after three o'clock

in the afternoon, and continued till evening. The next morning was foggy; and as the English observed that many

of the enemy had lost their way in the night and in the mist, they employed a stratagem to bring them into their

power: they erected on the eminences some French standards which they had taken in the battle; and all who were

allured by this false signal were put to the sword, and no quarter given them. In excuse for this inhumanity,

it was alleged that the French King had given like orders to his troops; but the real reason probably was, that

the English, in their present situation, did not choose to be incumbered with prisoners. On the day of battle

and on the ensuing, there French fell, by a moderate computation, 1,200 French knights, 1,400 gentlemen, 4,000

men-at-arms, besides about 30,000 of inferior rank: many of the principal nobility of France, the Dukes of Lorraine

and Bourbon, the Earls of Flanders, Blois, Vaudemont, Aumale, were left on the field of battle.

The kings also of Bohemia and Majorca were slain. The fate of the former was remarkable: he was blind from age;

but being resolved to hazard his person, and set an example to others, he ordered the reins of his bridle to be

tied on each side to the horses of two gentlemen of his train; and his dead body, and those of his attendants,

were afterward found among the slain, with their horses standing by them in that situation. His crest was three

ostrich feathers; and his motto these German words, Ich dien (I serve): which the Prince of Wales and his

successors adopted, in memorial of this great victory. The action may seem no less remarkable for the small loss

sustained by the English, than for the great slaughter of the French: there were killed in it only one esquire

and three knights, and very few of inferior rank; a demonstration, that the prudent disposition planned by Edward,

and the disorderly attack made by the French, had rendered the whole rather a rout than a battle; which was indeed

the common case with engagements in those times.

The kings also of Bohemia and Majorca were slain. The fate of the former was remarkable: he was blind from age;

but being resolved to hazard his person, and set an example to others, he ordered the reins of his bridle to be

tied on each side to the horses of two gentlemen of his train; and his dead body, and those of his attendants,

were afterward found among the slain, with their horses standing by them in that situation. His crest was three

ostrich feathers; and his motto these German words, Ich dien (I serve): which the Prince of Wales and his

successors adopted, in memorial of this great victory. The action may seem no less remarkable for the small loss

sustained by the English, than for the great slaughter of the French: there were killed in it only one esquire

and three knights, and very few of inferior rank; a demonstration, that the prudent disposition planned by Edward,

and the disorderly attack made by the French, had rendered the whole rather a rout than a battle; which was indeed

the common case with engagements in those times.

The great prudence of Edward appeared not only in obtaining this memorable victory, but in the measures which he

pursued after it. Not elated by his present prosperity, so far as to expect the total conquest of France, or even

that of any considerable provinces; he purposed only to secure such an easy entrance into that kingdom as might

afterward open the way to more moderate advantages. He knew the extreme distance of Guienne: he had experienced

the difficulty and uncertainty of penetrating on the side of the Low Countries, and had already lost much of his

authority over Flanders by the death of D'Arteville, who had been murdered by the populace themselves, his former

partisans, on his attempting to transfer the sovereignty of that province to the Prince of Wales. The King, therefore,

limited his ambition to the conquest of Calais: and after the interval of a few days, which he employed in interring

the slain, he marched forward with his victorious army, and presented himself before the place."

Excerpted from:

Hume, David and Tobias Smollett. History of England. Vol 2.

London: A. J. Valey, 1834. 333-339.

Other Local Resources:

Books for further study:

Allmand, Christopher. The Hundred Years War: England and France at War.

Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Ayton, Andrew and Philip Preston. The Battle of Crécy, 1346.

Boydell Press, 2007.

Barber, Richard. Edward III and the Triumph of England.

Penguin Books, 2014.

Burne, Alfred H. The Crécy War.

Frontline Books, 2016.

Livingston, Michael. Crécy: Battle of Five Kings.

Osprey Publishing, 2007.

Livingston, Michael and Kelly DeVries, eds. The Battle of Crécy: A Casebook.

Liverpool University Press, 2016.

Nicolle, David. Crécy 1346: Triumph of the Longbow.

Osprey Publishing, 2000.

Seward, Desmond. The Hundred Years War: The English in France 1337-1453.

Penguin, 1999.

The Battle of Crécy on the Web:

| to the Battle of Crécy |

Site ©1996-2023 Anniina Jokinen. All rights reserved.

This page was created on September 22, 2010. Last updated March 4, 2023.

|

Index of Encyclopedia Entries:

Medieval Cosmology

Prices of Items in Medieval England

Edward II

Isabella of France, Queen of England

Piers Gaveston

Thomas of Brotherton, E. of Norfolk

Edmund of Woodstock, E. of Kent

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Lancaster, Earl of Lancaster

Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster

Roger Mortimer, Earl of March

Hugh le Despenser the Younger

Bartholomew, Lord Burghersh, elder

Hundred Years' War (1337-1453)

Edward III

Philippa of Hainault, Queen of England

Edward, Black Prince of Wales

John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall

The Battle of Crécy, 1346

The Siege of Calais, 1346-7

The Battle of Poitiers, 1356

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster

Edmund of Langley, Duke of York

Thomas of Woodstock, Gloucester

Richard of York, E. of Cambridge

Richard Fitzalan, 3. Earl of Arundel

Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March

The Good Parliament, 1376

Richard II

The Peasants' Revolt, 1381

Lords Appellant, 1388

Richard Fitzalan, 4. Earl of Arundel

Archbishop Thomas Arundel

Thomas de Beauchamp, E. Warwick

Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford

Ralph Neville, E. of Westmorland

Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk

Edmund Mortimer, 3. Earl of March

Roger Mortimer, 4. Earl of March

John Holland, Duke of Exeter

Michael de la Pole, E. Suffolk

Hugh de Stafford, 2. E. Stafford

Henry IV

Edward, Duke of York

Edmund Mortimer, 5. Earl of March

Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland

Sir Henry Percy, "Harry Hotspur"

Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester

Owen Glendower

The Battle of Shrewsbury, 1403

Archbishop Richard Scrope

Thomas Mowbray, 3. E. Nottingham

John Mowbray, 2. Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Fitzalan, 5. Earl of Arundel

Henry V

Thomas, Duke of Clarence

John, Duke of Bedford

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

Richard, Earl of Cambridge

Henry, Baron Scrope of Masham

William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Montacute, E. Salisbury

Richard Beauchamp, E. of Warwick

Henry Beauchamp, Duke of Warwick

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter

Cardinal Henry Beaufort

John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset

Sir John Fastolf

John Holland, 2. Duke of Exeter

Archbishop John Stafford

Archbishop John Kemp

Catherine of Valois

Owen Tudor

John Fitzalan, 7. Earl of Arundel

John, Lord Tiptoft

Charles VII, King of France

Joan of Arc

Louis XI, King of France

Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy

The Battle of Agincourt, 1415

The Battle of Castillon, 1453

The Wars of the Roses 1455-1485

Causes of the Wars of the Roses

The House of Lancaster

The House of York

The House of Beaufort

The House of Neville

The First Battle of St. Albans, 1455

The Battle of Blore Heath, 1459

The Rout of Ludford, 1459

The Battle of Northampton, 1460

The Battle of Wakefield, 1460

The Battle of Mortimer's Cross, 1461

The 2nd Battle of St. Albans, 1461

The Battle of Towton, 1461

The Battle of Hedgeley Moor, 1464

The Battle of Hexham, 1464

The Battle of Edgecote, 1469

The Battle of Losecoat Field, 1470

The Battle of Barnet, 1471

The Battle of Tewkesbury, 1471

The Treaty of Pecquigny, 1475

The Battle of Bosworth Field, 1485

The Battle of Stoke Field, 1487

Henry VI

Margaret of Anjou

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York

Edward IV

Elizabeth Woodville

Richard Woodville, 1. Earl Rivers

Anthony Woodville, 2. Earl Rivers

Jane Shore

Edward V

Richard III

George, Duke of Clarence

Ralph Neville, 2. Earl of Westmorland

Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick

Edward Neville, Baron Bergavenny

William Neville, Lord Fauconberg

Robert Neville, Bishop of Salisbury

John Neville, Marquis of Montagu

George Neville, Archbishop of York

John Beaufort, 1. Duke Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2. Duke Somerset

Henry Beaufort, 3. Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 4. Duke Somerset

Margaret Beaufort

Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond

Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke

Humphrey Stafford, D. Buckingham

Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

Humphrey Stafford, E. of Devon

Thomas, Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby

Sir William Stanley

Archbishop Thomas Bourchier

Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex

John Mowbray, 3. Duke of Norfolk

John Mowbray, 4. Duke of Norfolk

John Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Henry Percy, 2. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 3. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 4. E. Northumberland

William, Lord Hastings

Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter

William Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford

Thomas de Clifford, 8. Baron Clifford

John de Clifford, 9. Baron Clifford

John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester

Thomas Grey, 1. Marquis Dorset

Sir Andrew Trollop

Archbishop John Morton

Edward Plantagenet, E. of Warwick

John Talbot, 2. E. Shrewsbury

John Talbot, 3. E. Shrewsbury

John de la Pole, 2. Duke of Suffolk

John de la Pole, E. of Lincoln

Edmund de la Pole, E. of Suffolk

Richard de la Pole

John Sutton, Baron Dudley

James Butler, 5. Earl of Ormonde

Sir James Tyrell

Edmund Grey, first Earl of Kent

George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent

John, 5th Baron Scrope of Bolton

James Touchet, 7th Baron Audley

Walter Blount, Lord Mountjoy

Robert Hungerford, Lord Moleyns

Thomas, Lord Scales

John, Lord Lovel and Holand

Francis Lovell, Viscount Lovell

Sir Richard Ratcliffe

William Catesby

Ralph, 4th Lord Cromwell

Jack Cade's Rebellion, 1450

Tudor Period

King Henry VII

Queen Elizabeth of York

Arthur, Prince of Wales

Lambert Simnel

Perkin Warbeck

The Battle of Blackheath, 1497

King Ferdinand II of Aragon

Queen Isabella of Castile

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

King Henry VIII

Queen Catherine of Aragon

Queen Anne Boleyn

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Anne of Cleves

Queen Catherine Howard

Queen Katherine Parr

King Edward VI

Queen Mary I

Queen Elizabeth I

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond

Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

James IV, King of Scotland

The Battle of Flodden Field, 1513

James V, King of Scotland

Mary of Guise, Queen of Scotland

Mary Tudor, Queen of France

Louis XII, King of France

Francis I, King of France

The Battle of the Spurs, 1513

Field of the Cloth of Gold, 1520

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador

The Siege of Boulogne, 1544

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex

Thomas, Lord Audley

Thomas Wriothesley, E. Southampton

Sir Richard Rich

Edward Stafford, D. of Buckingham

Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire

George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford

John Russell, Earl of Bedford

Thomas Grey, 2. Marquis of Dorset

Henry Grey, D. of Suffolk

Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester

George Talbot, 4. E. Shrewsbury

Francis Talbot, 5. E. Shrewsbury

Henry Algernon Percy,

5th Earl of Northumberland

Henry Algernon Percy,

6th Earl of Northumberland

Ralph Neville, 4. E. Westmorland

Henry Neville, 5. E. Westmorland

William Paulet, Marquis of Winchester

Sir Francis Bryan

Sir Nicholas Carew

John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford

Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral

Edward Seymour, Protector Somerset

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury

Henry Pole, Lord Montague

Sir Geoffrey Pole

Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Manners, Earl of Rutland

Henry Bourchier, 2. Earl of Essex

Robert Radcliffe, 1. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 2. Earl of Sussex

George Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon

Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter

George Neville, Baron Bergavenny

Sir Edward Neville

William, Lord Paget

William Sandys, Baron Sandys

William Fitzwilliam, E. Southampton

Sir Anthony Browne

Sir Thomas Wriothesley

Sir William Kingston

George Brooke, Lord Cobham

Sir Richard Southwell

Thomas Fiennes, 9th Lord Dacre

Sir Francis Weston

Henry Norris

Lady Jane Grey

Sir Thomas Arundel

Sir Richard Sackville

Sir William Petre

Sir John Cheke

Walter Haddon, L.L.D

Sir Peter Carew

Sir John Mason

Nicholas Wotton

John Taylor

Sir Thomas Wyatt, the Younger

Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio

Cardinal Reginald Pole

Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester

Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London

Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London

John Hooper, Bishop of Gloucester

John Aylmer, Bishop of London

Thomas Linacre

William Grocyn

Archbishop William Warham

Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham

Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester

Edward Fox, Bishop of Hereford

Pope Julius II

Pope Leo X

Pope Clement VII

Pope Paul III

Pope Pius V

Pico della Mirandola

Desiderius Erasmus

Martin Bucer

Richard Pace

Christopher Saint-German

Thomas Tallis

Elizabeth Barton, the Nun of Kent

Hans Holbein, the Younger

The Sweating Sickness

Dissolution of the Monasteries

Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536

Robert Aske

Anne Askew

Lord Thomas Darcy

Sir Robert Constable

Oath of Supremacy

The Act of Supremacy, 1534

The First Act of Succession, 1534

The Third Act of Succession, 1544

The Ten Articles, 1536

The Six Articles, 1539

The Second Statute of Repeal, 1555

The Act of Supremacy, 1559

Articles Touching Preachers, 1583

Queen Elizabeth I

William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Nicholas Bacon

Sir Thomas Bromley

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick

Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon

Sir Thomas Egerton, Viscount Brackley

Sir Francis Knollys

Katherine "Kat" Ashley

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester

George Talbot, 6. E. of Shrewsbury

Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury

Gilbert Talbot, 7. E. of Shrewsbury

Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Robert Sidney

Archbishop Matthew Parker

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich

Sir Christopher Hatton

Edward Courtenay, E. Devonshire

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Thomas Radcliffe, 3. Earl of Sussex

Henry Radcliffe, 4. Earl of Sussex

Robert Radcliffe, 5. Earl of Sussex

William Parr, Marquis of Northampton

Henry Wriothesley, 2. Southampton

Henry Wriothesley, 3. Southampton

Charles Neville, 6. E. Westmorland

Thomas Percy, 7. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 8. E. Northumberland

Henry Percy, 9. E. Nothumberland

William Herbert, 1. Earl of Pembroke

Charles, Lord Howard of Effingham

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk

Henry Howard, 1. Earl of Northampton

Thomas Howard, 1. Earl of Suffolk

Henry Hastings, 3. E. of Huntingdon

Edward Manners, 3rd Earl of Rutland

Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland

Francis Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland

Henry FitzAlan, 12. Earl of Arundel

Thomas, Earl Arundell of Wardour

Edward Somerset, E. of Worcester

William Davison

Sir Walter Mildmay

Sir Ralph Sadler

Sir Amyas Paulet

Gilbert Gifford

Anthony Browne, Viscount Montague

François, Duke of Alençon & Anjou

Mary, Queen of Scots

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell

Anthony Babington and the Babington Plot

John Knox

Philip II of Spain

The Spanish Armada, 1588

Sir Francis Drake

Sir John Hawkins

William Camden

Archbishop Whitgift

Martin Marprelate Controversy

John Penry (Martin Marprelate)

Richard Bancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury

John Dee, Alchemist

Philip Henslowe

Edward Alleyn

The Blackfriars Theatre

The Fortune Theatre

The Rose Theatre

The Swan Theatre

Children's Companies

The Admiral's Men

The Lord Chamberlain's Men

Citizen Comedy

The Isle of Dogs, 1597

Common Law

Court of Common Pleas

Court of King's Bench

Court of Star Chamber

Council of the North

Fleet Prison

Assize

Attainder

First Fruits & Tenths

Livery and Maintenance

Oyer and terminer

Praemunire

The Stuarts

King James I of England

Anne of Denmark

Henry, Prince of Wales

The Gunpowder Plot, 1605

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset

Arabella Stuart, Lady Lennox

William Alabaster

Bishop Hall

Bishop Thomas Morton

Archbishop William Laud

John Selden

Lucy Harington, Countess of Bedford

Henry Lawes

King Charles I

Queen Henrietta Maria

Long Parliament

Rump Parliament

Kentish Petition, 1642

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford

John Digby, Earl of Bristol

George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax

Robert Devereux, 3rd E. of Essex

Robert Sidney, 2. E. of Leicester

Algernon Percy, E. of Northumberland

Henry Montagu, Earl of Manchester

Edward Montagu, 2. Earl of Manchester

The Restoration

King Charles II

King James II

Test Acts

Greenwich Palace

Hatfield House

Richmond Palace

Windsor Palace

Woodstock Manor

The Cinque Ports

Mermaid Tavern

Malmsey Wine

Great Fire of London, 1666

Merchant Taylors' School

Westminster School

The Sanctuary at Westminster

"Sanctuary"

Images:

Chart of the English Succession from William I through Henry VII

Medieval English Drama

London c1480, MS Royal 16

London, 1510, the earliest view in print

Map of England from Saxton's Descriptio Angliae, 1579

London in late 16th century

Location Map of Elizabethan London

Plan of the Bankside, Southwark, in Shakespeare's time

Detail of Norden's Map of the Bankside, 1593

Bull and Bear Baiting Rings from the Agas Map (1569-1590, pub. 1631)

Sketch of the Swan Theatre, c. 1596

Westminster in the Seventeenth Century, by Hollar

Visscher's View of London, 1616

Larger Visscher's View in Sections

c. 1690. View of London Churches, after the Great Fire

The Yard of the Tabard Inn from Thornbury, Old and New London

|

|